History

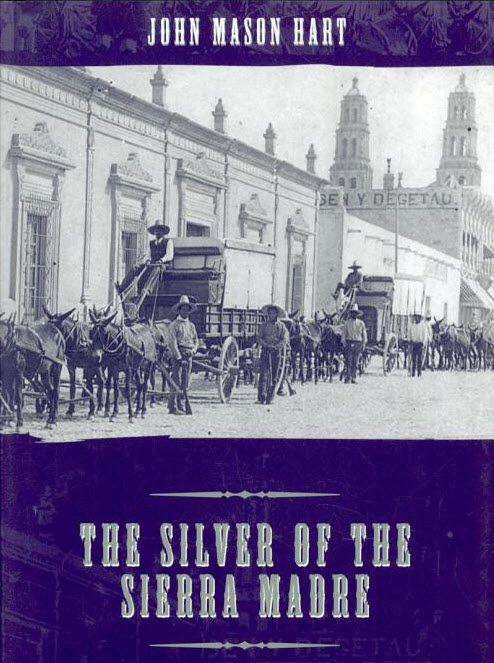

The history of Batopilas makes an interesting and compelling story. In 1522 Spaniards first discovered silver in Mexico, at Taxco in the state of Guerrero. Within two years, silver was being minded at Pachuca; in 1540 the great deposit at Zacatecas was discovered and in 1548 the astoundingly rich silver deposits at Guanajuato were found. The King of Spain received regularly his one-fifth share of the silver bullion, as well as impressive natural specimens of native silver. It became clear to the Spanish that Mexico was a treasure house of silver. In the following decades, Mexico was thoroughly prospected by the Spanish, and modern mining men claim that no important deposits which crop out were missed (Naica is an exception), though some of their discoveries were abandoned as uneconomical to mine at the the time.

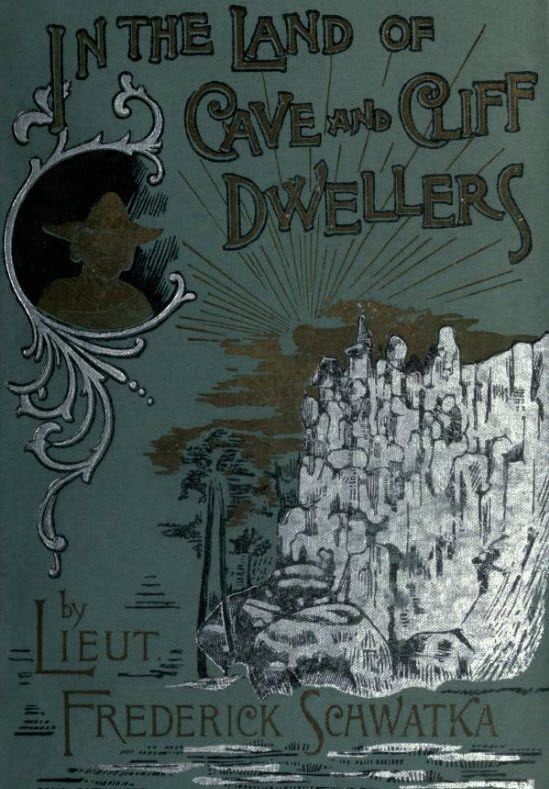

In 1632 a small band of Spanish adelantados or ‘advance guards’ explored the valley of the Batopilas River and found native silver. The discovery point was apparently in the river itself, near the bank, where pure, glistening white silver had been stream-polished and kept from tarnishing. They named it the Nevada mine because of this snow-white metal, nevada meaning ‘snowy’ or ‘snow-capped’ in Spanish. Specimens from the discovery were packed out and conveyed to the King of Spain in Madrid, who was presumably impressed. Spanish immigration into Mexico increased significantly as a result of the news.

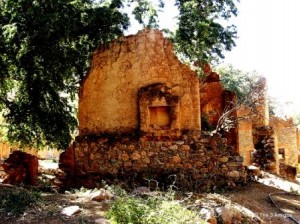

A village developed on the banks of the river, and mining began. Knowledge of those early years is sparse because fires in 1740 and again in 1845 destroyed many records. It is known, however, that one of the Spaniards, Don Rafael Alonzo de Pastrana, encountered a bonanza of silver in his Nuestra Senora del Pilar mine (ca.1730) which yielded him 40,000 pesos weekly for many years. At one time, the wealthy Pastrana is said to have invited the Bishop of Durango to visit Batopilas; when the Bishop arrived, he found that Pastrana had laid for him a solid silver sidewalk of ingots leading from the church to the house where the Bishop was to stay. The clergyman, so the story goes, was horrified by this ostentatious display and reproved Pastrana for his vanity (W.D. Pearce in Griggs, 1907). Pastrana died to 1760, by which time the main pocket was exhausted and much of the mine had caved in. Even today, however, ancient workings in the Pastrana mine which are still accessible can be seen to have been continuously stopped for over 250 meters (800 feet) in what was rich native silver (Brodie, 1909b).

In 1775 a Mexican miner by the name of Cristobal Perez obtained the rights to work the San Antonio mine. he subsequently struck a bonanza pocket of silver which lasted for 14 years of continuous mining and yielded many millions of dollars. Perez and his son became widely known as two of the most important personages in that part of Mexico, and many stories were told of their wild extravagances. The stories were probably true, because by the time the son died in 1814, the entire fortune had been spent (Brodie, 1910).

In the 1790’s another Spaniard, Don Angel Bustamante, came to Batopilas as a merchant and gradually became involved in mining. He tried many times to find a silver pocket and failed. Persevering further, however, he acquired a claim on the Carmen mine and eventually did strike a bonanza which, authorities claim, yielded him a minimum of $14 million. with his wealth he returned to Spain and purchased a Marquisate (becoming the Marquis de Batopilas), though his employees continued to operate his mines for him until 1824 (Tod, 1907; Brodie, 1909).

During the early 1800’s, Baron Alexander von Humboldt traveled through Mexico and published numerous reports on the mines. Of Batopilas, he wrote: Native silver has been found in considerable masses sometimes weighing more than 440 pounds in the mines of Batopilas. it is no doubt true that blocks of silver of enormous weight have been extracted (von Humboldt, 1824).

In the 1820’s the Spanish were expelled from Mexico in a bloody war of rebellion, and Batopilas went into recession. The owner of the San Antonio min, Jose Esparza, officially filed his abandonment of the property in 1820, stating that the town was in a most miserable condition, and that only the Cata mine and the Martinez mine remained active. Little work was accomplished in the district during the first years following the Spanish expulsion (Brodie, 1909).

In the 1820’s the Spanish were expelled from Mexico in a bloody war of rebellion, and Batopilas went into recession. The owner of the San Antonio min, Jose Esparza, officially filed his abandonment of the property in 1820, stating that the town was in a most miserable condition, and that only the Cata mine and the Martinez mine remained active. Little work was accomplished in the district during the first years following the Spanish expulsion (Brodie, 1909).

Then, in 1842, a woman of ‘strong character’ arrived in Batopilas. She was Dona Natividad Ortez and with the help of her Indian associate, Nepomuceno Avila, she began work at a number of mines. Within a short time, the Santo Domingo, San Nestor and Animas mines had yielded her about $300,000 (Tod, 1907). Under her management, new veins were discovered and mines begun, including the Todos Santos, San Pedro and La Aurora mines. Batopilas was in full swing again.

The San Antonio mine came into the possession of Manuel Mendazona in 1852. He was a merchant from Culiacan who had made some money in the mining districts of Dolores and Guadalupe y Calvo. Among his first projects was a tunnel, called the San Miguel tunnel, which was designed to cut the veins of the Carmen and San Antonio mines near their lowest workings, at a depth of about 150 meters below the surface. A tunnel greatly reduced the cost of removing ore from higher workings because hoisting was eliminated. Before the tunnel could be competed, however, Mendazona died in 1856, and in 1861 the property was sold to an American company under the direction of John R. Robinson.

Robinson completed the tunnel to the San Antonio mine, which he had initially intended to work. Along the way, however, the San Miguel tunnel cut a blind vein. At first it was not considered important, but it did show some minor indications of silver. therefore, following completion of the tunnel, Robinson decided to work the new vein for a distance and see what could be found. What he found as a major bonanza of native silver which came to be called the Veta Grande, or ‘Great Vein’. This vein was so rich, and its fame subsequently so widespread, that bandit chiefs arrived periodically to extort tribute; one even seized the mine for two months and , with a crew of 300 men, extracted $100,000 in silver before tiring of the miner’s life (Tod, 1907; Brodie, 1909).

Robinson continued to work his holdings in a small way for 19 years. During this time the town slowly grew until, in 1877, it was made the capital of the Canton of Andres del Rio (Tod, 1907). Robinson sold the San Miguel mine in 1880 to another American, Alexander R. Shepherd, the former (and last) governor of Washington D.C. Shepherd paid $600,000 for the property and moved to Batopilas with his family to take personal charge of the operations. Over 350 other mining claims covering 31 square kilometers (12 square miles) were eventually acquired and consolidated as the Batopilas Mining Company. in 1886 a concession was granted the company by the Mexican government which gave effective control of the entire district. Shepherd ran the operation with the help of his sons, until his death in 1902.

Operations under Shepherd were generally prosperous despite some fluctuations in production and the price of silver. During the first years following 1880, about $1 million were paid in dividends, and the town grew in population from 400 to over 5,000 inhabitants. From 1880 to 1906, the production of silver was estimated at 19.5 million ounces (Shepherd, 1935).

Lodes of rich native silver ore were extremely profitable when found, but very irregular in distribution and difficult to locate. Mining generally followed the veins, which tended to be barren over great lengths between lodes. When heavy silver masses were encountered, usually only a day or two elapsed between blasting of the pocket and casting of the finished silver ingots.

Lamb (1908) mentions an encounter between Alexander Shepherd and a visiting mining engineer who was taking samples from the various veins in order to determine how much ore was ‘in sight’. Shepherd at length pointed out to the engineer that such a procedure was useless at Batopilas. ‘We have no ore in sight’ he said. ‘Just as soon as it gets in sight, we take it out of sight’.

It was the custom for each mine superintendent to telephone headquarters each afternoon and request as many mules be sent up as pocket silver found that day would require for transport. The ore was so unpredictable in its occurrence that sometimes only two mules might be required, and at other times 30 mules might not be enough.

Lamb (1908) relates another story about a time when funds were low, no ore was ‘in sight’ and $90,000 was owed the bank on a draft Shepherd had written recently in New York. The report from the mine at 1 p.m. was gloomy…only three mules were required. Just as the staff was becoming seriously worried, another call came in from the mine. The excited superintendent was asking for more mules. ‘It looks now like about 30 loads, but we’re not through it yet. It’s going to be hell to get out; it will not shoot; not enough rock mixed in with the silver. Send a crew from the shop with coldcutters!’

During his tenure, Shepherd saw to the construction of numerous buildings and facilities totaling well over $2 million in cost. Stamp mills, Bartlett concentrators, electric generators, air compressors, a small dam for hydroelectric power, a masonry aqueduct 3 kms long, amalgamating and retorting facilities, a foundry capable of making castings up to 1100 kg (2,500 pounds), an assay office, administrative office, dormitories, a boarding house, a hospital, a bridge over the river and an 800-meter aerial tram were all constructed entirely of materials packed in on mule-back.

The ground held up well, and timbering was hardly ever used except in chutes and other functional constructions.

Shepherd’s son, Grant, was five years old when the family moved to Batopilas. Fifty-eight years later, he published his memoirs, entitled The Silver Magnet; Fifty Years in a Mexican Silver Mine. His story makes fascinating reading, and gives a rare glimpse into the nature of life and mining at Batopilas. Following are some excerpts from Grant Shepherd’s memoirs (1938) of his days at Batopilas, between the years 1880 and 1914.

Shepherd’s son, Grant, was five years old when the family moved to Batopilas. Fifty-eight years later, he published his memoirs, entitled The Silver Magnet; Fifty Years in a Mexican Silver Mine. His story makes fascinating reading, and gives a rare glimpse into the nature of life and mining at Batopilas. Following are some excerpts from Grant Shepherd’s memoirs (1938) of his days at Batopilas, between the years 1880 and 1914.

When a man in the year 1880 took over a mining business in a locality such as Batopilas, the difficulties were many. There was no rail connection for 600 miles until 1883, when the Mexican Central got as far as El Paso, Texas. Then the distance between the mines and the railroad was reduced to 300 or more miles. But those 300 miles had to be traveled and freight had to be transported across them, for the first 185 miles on the backs of mules, and the last 150 miles on wagons or ox-carts. After a few years’ residence in Batopilas, we accepted the unavoidable mountain trip to Chihuahua City as a necessary evil, a part of the essential game of getting the silver bullion from the mines to the market, and, in turn, securing the safe arrival into Batopilas of supplies.

The monthly bullion trains always took not less than 50 bars of silver bullion worth about $60,000USD; more often they conveyed 100 bars; on special and unusual occasions they had as many as 200 bars or even more. Since each mule carries only two bars of silver, you will readily understand that these trains were made up of from 30 to 100 or more mules.

As a small boy, I used to come into Chihuahua sitting on the driver’s seat of a Concord stagecoach filled with silver bullion, with fourteen mules hitched to it and going at full gallop. The long whip of the cochero would be popping while we swung dizzily round the corners of the narrow streets of the town. We would pull up with a flourish in front of the Banco Minero. The coach I rode was the leading stage, and it was followed by several more, all of them loaded with silver bars.

There were five major mines being worked under my father; the San Miguel, Roncesvalles, Camuchin, Todos Santos and La Decubridora. Ores from each of the mines had to be treated separately and an exact account kept.

Seventy-five to eighty percent of all silver values contained in Batopilas ore are pure native silver, occurring in irregular masses, plates and crystals imbedded in vein calcite. When the rich pockets or bonanzas are encountered there is always a great amount of calcite. The native silver crystals, which have been covered by this crystallization that is quite transparent, are entirely imbedded in it. It is very beautiful.

I worked at various times in each and every mine operated by the company, including the Porfirio Diaz tunnel. ti gave me a fine opportunity to study and better understand the vein groups and the variety of ores. Although it may seem strange, in the San Miguel group (the deposits worked through the San Miguel tunnel), the ores of the Veta Grande, Mesquite, Carmen and San Antonio were very dissimilar in appearance. This was because of the divergence of content and crystallization of the various minerals. The ores of the Porfirio Diaz group were also distinctive in appearance; we would pick up a piece of ore and tell from its appearance which vein in came from, and sometimes even which level on a certain vein.

Leather was used in immense amounts, for making zurrones, bags for packing of the high-grade ores. Silver sulfide concentrates, after being sewn up tight in the canvases, were finally sewn into bags of well-wetted rawhide, which when dry took an ax to open, and with which covering they went all the way to Aurora, Illinois, for smelting.

When my father took over in 1880, the surface outcrops had been worked as deep as possible by primitive methods. On the backs of men, it is possible only to carry ores up ladders for 500 feet more or less. The best peon will carry 100 to 150 pounds in a zurron up a distance of 500 to 1000 feet of ladders…but he cannot make many such trips a day. hence the cost becomes prohibitive.

We used horse whims, then steam hoists; afterwards came gasoline hoists and compressed air drills, and for many years the longest mining tunnel in Mexico, the Porfirio Diaz tunnel. Our total of underground workings was over 75 miles.

The Porfirio Diaz tunnel required several years to drive. It cut all the veins found on the western side of the river. From the portal to the point where it tapped the Roncesvalles vein is 7050 feet. It is continued on the vein and to the Todos Santos vein for 2000 feet more. The old shafts and workings from above are connected with the tunnel; therefore, instead of being compelled to hoist them, the ores roll down to tunnel level, making a much more economical proceeding altogether.

The Porfirio Diaz tunnel required several years to drive. It cut all the veins found on the western side of the river. From the portal to the point where it tapped the Roncesvalles vein is 7050 feet. It is continued on the vein and to the Todos Santos vein for 2000 feet more. The old shafts and workings from above are connected with the tunnel; therefore, instead of being compelled to hoist them, the ores roll down to tunnel level, making a much more economical proceeding altogether.

At the Worlds Fair in Chicago in 1893, our ores from Batopilas took the premium in their class. The biggest piece we exhibited weighed 380 pounds. We had three of our very strongest pack mules bring it out with the regular pack train, and they made the customary 40 miles each day. This was done by changing the load every ten miles, and it was a tremendous nuisance.

The natives thought electric lights to be almost magical when my father first had electricity installed in Batopilas. Never in their lives had they seen or pictured to themselves an electric light. The first night the electric plant was put into commission, one of the men was told to go out and touch a button to light up the place. Instead he got a box of matches and tried to screw off a glass bulb so he could apply a match to the wire!

It was my good fortune once to open up a very ancient mine that lay between two we were working. The company from which we had taken over in 1880 had no record of its existence, nor had we until my brother-in-law came across an ancient map of the San Miguel group in the Department of Mines in Mexico City. He wrote us about this discover, we investigated, and sure enough after a good deal of digging we found what had once been a tunnel entrance. It was plugged up with heavy stulls of pine whose timbers were over 15 inches in diameter. There were indications that very rich pockets of pretty good size had been taken from these workings, since in places the stopes were of considerable size. We discovered ladders of the old native type, made from a pole 15 or more inches in diameter with notches for steps cut at regular intervals.

Our ores were what is commonly known as high-grade, therefore, much watchfulness had to be exercised to prevent them from being filched. We had a group of trusted employees, native and foreign, who kept themselves on the thinnest edge of readiness to combat the ingenuity of those who hoped to add to their wages by stealing small amounts now and then and carrying them out of the mines on their persons. Some of the methods are worth relating: Say, for instance, you wear your hair quite long, and while you are turning the drill steel and it is cutting through rich silver ore, you must clean your hands of the drill mud. If you wipe your ands on your head, the long hair will get full of mud. When you go home and wash your hair in the basin, you will find you have washed out fine particles of silver…after you become expert, as much as a third of an ounce a day. Or suppose you are wearing the native sandal made of heavy sole leather. with patience and skill you can split the sole so as to make a thin pocket into which you can put an ounce of flattened native silver. Another way is to forego your dinner. Take you dinner of hash or beans into the mine in a porridge bowl covered with corn tortillas. Put the filched silver in the bottom of the bowl, under the beans and replace the tortillas. Look sick as you reach the mouth of the tunnel to searched; tell the gatekeeper and searcher that you did not eat your dinner because you had a ‘dolor muy fuerte’ in your stomach. There are other very unique methods.

It was not all beer and skittles during my thirty-odd years at Batopilas. At times silver went way down in price, we were heavily in debt, and we had overreached our overdraft at the Banco Minero in Chihuahua. But before matters hit the absolutely fatal spot at any one time, we would run into a bonanza of greater or lesser extent, and sometimes near the end of the month would knock out anywhere from fifty to a hundred thousand dollars in silver. One month we took out $450,000 in silver, and we had no air drills then. Did we work!

It was not until President Porfirio Diaz was overthrown that our company ever lost a bar of silver or a dollar of payroll money. That great liberator, the oppressed Francisco (Pancho) Villa, stole $38,000 worth of silver bars and buried them in a patio of a house in Chihuahua. He was afraid to convert them into cash, and later when this leader was not so strong in power we recovered the treasure.

After the Mexican Revolution began in 1910, the district went into a more of less permanent decline. The Shepherd sons ceased their operations for good in 1920 after several years of very low production. Intermittent minor production, some by the Santo Domingo Silver Company, took place from 1922 to 1929 and yielded a total of about 800,000 ounces (Gonzalez-Reyna, 1947).

In recent times (1974) a mill was installed at Batopilas by Francisco Lewels and Henry Ehrlinger (El Paso, Times 1975), but it was badly designed and could not process typical Batopilas ore. Gabriel Oaxaca and associates attempted a cyanide leaching operation at the Pastrana mine in 1981.

Local residents and occasional small-scale lessees continue to take a modest amount of silver from a few mines and by panning river gravel. As of 1980 only the Nevada Valenciana (New Nevada) and Caballo mines were being worked, but most of the mines in the district remain under claim, and many are reopened and reworked from time to time.

Throughout the history of Batopilas, production has been impressive. Tod (1909) estimates that the Pastrana mine yielded something less than 50 million ounces by itself since its discovery in 1730. LeBrun (in Brodie, 1910) estimates that the Carmen and San Antonio mines produced 8 million ounces prior to 1860. Gonzalez-Reyna (1947) gives a figure of 20 million ounces for the Los Tajos mine up to 1820, and another 27 million ounces for the district as a whole under Alexander Shepherd and sons (1880-1920). These few mines alone total up to more than 100 million ounces. Gonzalez-Reyna (1947) suggested an all-time total for the district of about 11 times the Shepherd total, or about 300 million ounces. This seems reasonable considering that no records at all are available for the first century of production, which must have yielded a significant amount.

Three hundred million ounces is a truly staggering amount of silver, equal to nearly 900 cubic meters! That is three times the amount of silver the Bisbee district produced in its lifetime, and seven times the total amount of silver mined at Kongsberg, Norway.